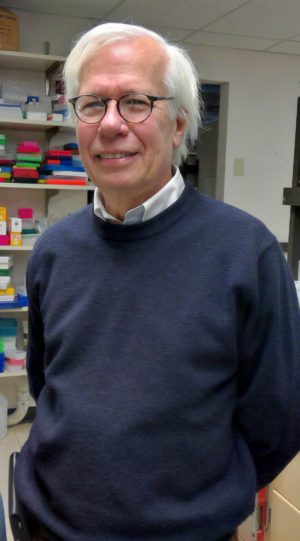

When it was pointed out to retiring James (Jay) Delmez, MD, Professor of Medicine, that he had been here for 39 years, he countered by saying it was much longer than that.

“I was born here,” he said. In his paced, quiet manner of speaking, Jay told the story of how his parents came to Barnes Hospital from Columbia, Missouri, because his mother’s obstetrician thought there might be complications with his delivery. “So, actually, it’s been 69 years!”

Jay received a BA from Washington University in 1969 and graduated with honors from the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, New York. In 1976, he completed his residency in internal medicine at Barnes and his nephrology fellowship in 1978. He was an attending physician on the renal consult service at Barnes, served as director of the Peritoneal Dialysis Program and taught at St. Luke’s Hospital in St. Louis from 1983-1985. Returning full-time to Washington University School of Medicine, he served as Medical Director of the Chromalloy American Kidney Center for the past 31 years. Jay received the Lifetime Achievement “Master Physician” Award from Barnes-Jewish Hospital in 2015.

Remembering the early days of the dialysis unit at Barnes, Jay says, “It was a lot smaller. When I was a fellow, the unit was on the second floor of Rand Johnson and in part of the old Barnes Hospital. A lot of tubing got disconnected … there was a lot of water on the floor. It was not the ideal situation.”

It was a different era back then. “Actually, the patients were allowed to smoke during treatments,” he says. “They had ashtrays taped to their chairs.” And it wasn’t just the patients. “I remember, as a resident, people smoking at grand rounds. Apparently, the thought was that you could be smarter … or look smarter … if you were smoking. It was, in retrospect, very bizarre.”

Jay also remembers the long working hours. “For internship, it was over 100 hours per week. That would not be allowed these days. It was crazy. It was a lot of sleepless nights. On call, if you could get 3 hours of sleep it was terrific. That was good, but you still had to work the next day until maybe midnight. It was not healthy. We had several of the interns get sick in the process.”

The hours did not get much better as a fellow. “You would be on for a week, then off for a week, then on for a week,” he says. “There were only two fellows on service, and we would cover acute kidney failure consults, chronic kidney failure consults and kidney transplant consults. But, the population was not nearly as large as it is now. It was obviously doable, because we did it, but it never crossed anybody’s mind that it was screwy hours!”

When Jay was an associate professor with tenure, he asked Marc Hammerman, the former chief of the division, what it would take to be full professor. “He [Marc] said you have to give a talk at a renal meeting that would be a major speech, or get an NIH grant,” says Jay. “So, I did both.”

One of the projects of which Jay is particularly proud was performed back when dialysis units were not routinely checking to see how well urea was removed. “We did a study asking all the dialysis units in the metropolitan St. Louis area to give us results of pre and post dialysis BUNs, the dialyzer type, the time they were on dialysis and other variables,” he says. “We wanted to see how well people were dialyzing who did not have a modeling of the amount of urea removed for treatment. To our surprise, half of the patients in the greater St. Louis area were not getting an adequate amount of urea removed. And that was probably going on across the country. It was not the standard of care to actually measure pre and post dialysis BUNs. It was just not done. The point is, unless you measure it, you can’t guess. It [eventually] became mandatory to measure pre and post dialysis BUNs and actually have a minimal value of what it should be. It took several years to set that premise.”

When asked if he had cleaned out his office, Jay replied with an emphatic YES. “The number of trash bags was amazing. But, there were classic articles, many written by [Eduardo] Slatopolsky and [Saulo] Klahr that I just couldn’t throw away. So, they are sitting in my office at home.”

Jay will have no problem keeping busy in retirement. “I’m really excited about some of the traveling we are going to do,” he says. “Antarctica. Jerusalem. Eventually, I think we are going to go to Peru and see the ruins there. We’ve lots of grandkids scattered all over the country, and now we can see them more.”

He also has plans to continue taking courses at Washington University’s adult education program  called Lifelong Learning. I took Digging Jerusalem about excavations in Jerusalem and its history. I’m also realizing that I don’t know history as well as I thought I did, so I’m reading a lot of history books on Jerusalem.” A course on the Renaissance has also piqued his interest. “Actually, if I could have figured out how to make a living [at it], I probably would have become an archeologist or an art historian.”

called Lifelong Learning. I took Digging Jerusalem about excavations in Jerusalem and its history. I’m also realizing that I don’t know history as well as I thought I did, so I’m reading a lot of history books on Jerusalem.” A course on the Renaissance has also piqued his interest. “Actually, if I could have figured out how to make a living [at it], I probably would have become an archeologist or an art historian.”

“It’s really been a terrific journey here,” he says. “I am going to miss the patients, as well as coworkers, nurses. I was just part of the team. There were some fabulous people here. It was, and is, a tremendous, fertile field of endeavor.”

On the future of the division, Jay says, “I think there is one way this division is going and it’s through the roof! I think we have a really good chief [in Benjamin Humphreys].”

What advice does Jay have for a young nephrologist? “My only words of wisdom are: Work hard, keep an open mind, and be cheerful!”